The first Vasaloppet

Anders Pers, from Mora, is the father of Vasaloppet. It was from his thoughts that the world’s biggest ski race was born. He wrote about the contemporary interest in skiing and linked it to Gustav Eriksson Vasa’s flight on skis from Mora towards Norway in 1521.

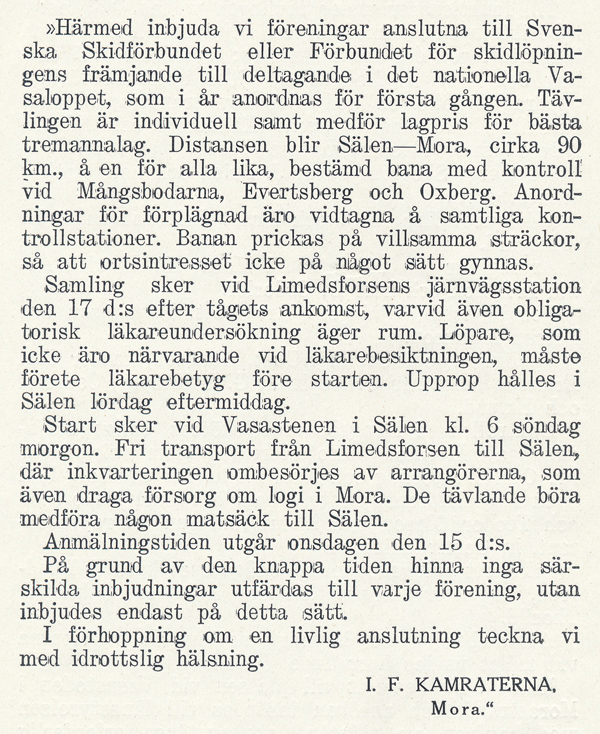

In an article in a local newspaper, Vestmanlands Läns Tidning, on 10th February 1922, he launched the idea of a Vasalopp. The national newspaper, Dagens Nyheter, reprinted his article the day after and, at the same time, gave its support for a long ski race, a test of endurance, as a commemoration of Gustav Vasa. After some considerable press debate, both for and against the idea, IFK Mora’s Board decided on 5th March to run a trial race, if there was some suitable financial backing. Dagens Nyheter donated 1,000 crowns to the arrangers and thus made it possible for the first Vasaloppet to be run on Sunday 19th March 1922.

Carl Emmanuel Berg from Göta in Karlstad was the first to register for Vasaloppet, on March 10th. In total 139 registrations came in to the competition secretariat by telegraph and telephone. 119 skiers came to the start, among them some of the foremost in Sweden: Per-Erik “Särna” Hedlund, Strål Lars Eriksson, IFK Mora, Jonas Persson, Arbrå, and Oskar Lindberg from Norsjö in Västerbotten.

At precisely 6.04 am, the race steward, Johan Westling, flagged the Vasalopps skiers off from Olnispagården on the west side of the river in Sälen. 7 hours 32 minutes and 49 seconds later the victor reached the goal in Mora after 90 kms skiing in sleet and snow. And it was Ernst Alm, from Norsjö IF, who won, five minutes before Oskar Lindberg, from the same club.

Anders Pers’ article

Friday, February 10, 1922, editor Anders Pers writes the following in the Vestmanlands Läns Tidning newspaper under the headline ”A national ski race”:

”This winter should see more lively ski sports than ever thanks to the even winter and good snow down on the plains. This may give reason to recall that it is now 400 years since some skiing had momentous influence on the shaping of political events in Sweden. We refer to the first days of January in 1521, when Gustaf Eriksson Wasa had given up hope of rallying the Dalarna men against the Danish tyranny and was about to leave everything behind and escape into Norway when, as we know, the men of Dalarna repented and sent two of their best skiers to catch up with the fugitive: Engelbrekt from Morkarlby and Lars from Kättilbo, now Kättbo.

How Gustaf Eriksson travelled we do not know but it is probable that he went through the forests from village to village, going by whichever path. The distances were great and the land less inhabited than now. But we know that the two scouts were skiing. It was a prudent way of transport around these parts, same as now.

We do not know which way they took but some guesswork may be allowed. If Gustaf went to Kättbo, the nearest village would be Öje by, followed by Malung, which was an old settlement even then. If he’d gone to Älvdalen and Evertsberg to then continue towards western Dalarna he would have had a straighter path but less inhabited; or not inhabited at all. It’s probable that he went via Kättbo, north Venjan and Lima. Whichever path he travelled, the two scouts had to follow his tracks and, in any case, try to cut him off in Sälen in present-day Transtrand parish, as that would be the last inhabited place on the path to Norway, where the fugitive would surely pass.

This calculation was correct, and he was found in Sälen. It is futile to speculate how our country’s fate would have turned out, had this ski venture failed. But we have reason to rejoice that the Mora–Sälen ski race, around 80 kilometres, was concluded satisfactorily.

Why shouldn’t we take up Mora–Sälen as a national ski race, right now, as we are about to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Gustaf Eriksson’s liberation of Sweden? It was here that the pendulum swung the other way, towards victory for him and Sweden. And the race should be fully satisfactory, from a sporting point of view.

The race location is good in several regards. You can count on snow here, every winter. The terrain is such that skiers from our inland forests would be used to, and often better. The area is still sparsely inhabited but public roads are now kept open along the whole course, with the exception of 30 kilometres between Venjan and Lima, but there are winter roads here during the winter, as everywhere in the forests. The location is advantageous for men from Värmland, Dalarna, Härjedalen and Hälsingland, and the entire Bergslagen area; in other words, where people ski by nature. It’s well situated for people from Norrland too, given that it’s near the inland railway line, open for traffic this summer and going through Mora and Venjan. But it’s not so distant that it cannot be reached by railway for participants from, for example, Stockholm.

Perhaps an objection should be raised; the race is long. Yes, but the intention here is to have a real test of manhood. Of course it should be arranged with mandatory rests during the race, so that there’s no risk to anyone’s life or health. The area should also have resources to provide accommodation, even if no big city luxury hotels can be found.

Most big sporting events are held in the big cities. It is neither possible nor desirable to change this. Most large competitions are run from there, where the spirit of competition is high. However, it may be asked if this sport in particular, which comes from the forests and grand expanses, might not benefit from making those expanses the field of competition, which would make for a historic course unmatched by any other skiing country.

Note that the winner in the 60-km race was a man from Särna, i.e. a man from this very region. And note that most ski race winners in general be from these parts, Dalarna and Bergslagen, right where this national ski race would be held.”

(The man from Särna was Per Erik ”Särna” Hedlund, who had won the Nordic Games 60 km on February 7, 1922. The race also counted as the Swedish Championship. Our note.)

The article by editor Pers was partially reprinted with support in the national newspaper Dagens Nyheter the very next day, February 11, 1922, with the headline: ”NATIONAL SKI RACE, GUSTAF VASA’S COURSE FROM MORA TO SÄLEN! Grand project presented by Västmanlands Läns Tidning.” DN concluded their article with: ”What say the Swedish Ski Association? Here’s an opportunity to institute a classic race!”

Important dates, 1922

- Friday 10/2: Anders Pers in VLT: ”A national ski race”.

- Saturday 11/2: Article reprinted with support in Dagens Nyheter.

- Monday 13/2: Reprint in Mora Tidning.

- Friday 17/2: IFK Mora discusses the question at a meeting.

- Monday 27/2: A letter to the editor of Mora Tidning encourages IFK Mora to arrange the race. Mora-Kamraterna has a board meeting, concluding that they can organise the race, provided that the financials can be suitably arranged.

- Friday 3/3: Statement from IFK Mora about financial backing is included in a Dagens Nyheter article.

- Sunday 5/3: The board of IFK Mora decides to hold Vasaloppet 19/3 that same year. The deciding factor is that Dagens Nyheter makes 1,000 SEK available for the event. The skiing direction will be Sälen–Mora for reasons of safety and practicality.

- Monday 6/3: The invitation is developed.

- Tuesday 7/3: The invitation is published in Stockholm newspapers and in most rural newspapers the next day.

- Wednesday 10/3: The first participant is registered.

- Sunday 19/3: The first Vasaloppet starts in Sälen at 06:04. Out of 139 registrants, 119 arrive at the start and 117 finish the race. 5,000 spectators are present at the finish line in Mora. The concept of the Kranskulla comes into existence. Ernst Alm wins with a finishing time of 7.32.49.

The first Vasaloppet, March 19, 1922

The first registrations came to IFK Mora on March 10 with IF Göta from Karlstad registering Carl Emanuel Berg, noted as the first Vasaloppet skier, and Bollnäs GoIF registering three skiers. Then registrations started flowing in. The list of registrants counted 139 names when the train with skiers from Mora was due to leave on Friday, March 17, via Brintbodarne and Malung, with Limedsforsen as the end station.

Some had already headed to Sälen to have extra time to rest up, including three participants from IFK Norsjö – Oskar Lindberg, Ernst Alm and John Bergmark. At Limedsforsen around forty sleighs awaited to continue the northward journey. Torches lit the way and after near four hours the participants arrived and were accommodated in various villages in and around Sälen. ”Everywhere, skiers were welcomed with open arms and set tables awaited them.” In the Sälen school house around 80 of them met up for a late evening meal.

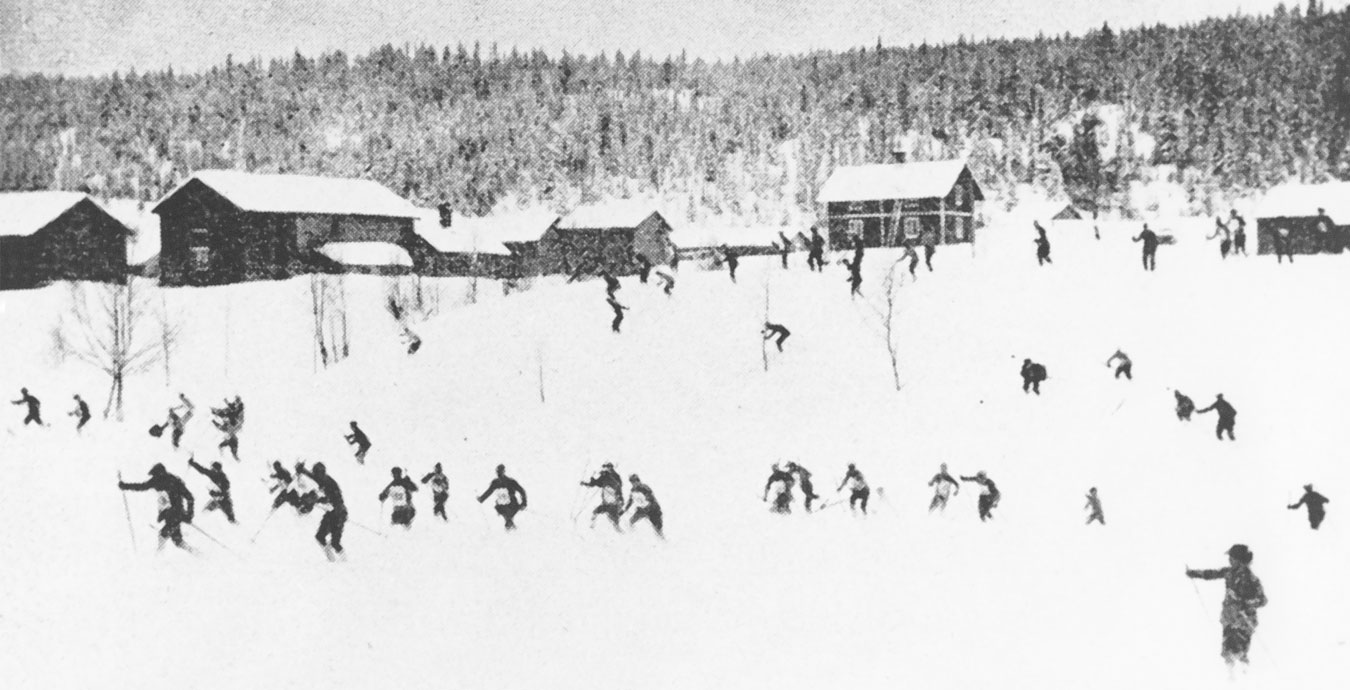

Saturday was dedicated to ski waxing. It was late in the winter and wet snow fell with temperatures above zero. A shared breakfast was served at 09:30. Number bibs were distributed because it was already time to film the skiers. At the time of the start the next morning it would be too dark, and the camera would be needed to film other parts of the race. So the start was simply faked a day early. At 13:00 there was a test start for the sake of the film crew. ”There was a rushing and hopping along forest paths, snow fields and slopes the likes of which Transtrand locals could hardly ever have seen before.” Supper was at 14:00 and an hour later, participants underwent medical examinations.

Temperatures sank overnight and the slush froze. 119 of the 139 registrants had turned up to the start in Sälen. The distance of the very first Vasaloppet was approximately 91 km. The same distance as a hundred years later, though only 5.8 km of the course runs along the same stretch today as in 1922.

The competition morning of March 19, 1922 started with breakfast at 04:30: ”A mountain of eggs and pancakes were consumed and small lakes of lingonberry jam,” DN wrote.

The start of the first Vasaloppet was held on level ground underneath Vasastenen, north of Olnispagården in Sälen. The start was meant to be at 06:00 but the checking of names, started at 05:45, took longer than expected and the start itself was at 06:04 with about 100 spectators on location.

They first skied over the river and the track then followed the country road down to Vörderås where it turned up towards Mångsbodarna, the first of three food checkpoints. Timekeeping was held at Evertsberg and Oxberg, but not in Mångsbodarna, where only placements were noted down. The first Vasaloppet participants to ever reach Mångsbodarna was Särna’s Swedish champion Per Erik Hedlund who arrived at 08:15; on his heels were Mora’s Strål Lars Eriksson and Djurgården’s Joel Eng. Ernst Alm was in sixth place.

Much later, Per Erik Hedlund remembered his equipment in the 1922 race: A couple of nine-foot skis weighing five to six kilos, equipped with one toe strap and one back strap. On his feet were pointed shoes of cloth. The long poles had no strap but were fitted with a rubber winding that provided better grip.

After a short food stop in Mångsbodarna, the leading group headed on towards Evertsberg. It started snowing and taking the lead in the track wasn’t comfortable. Speaking of the track… From Mångsbodarna the ”big country road” was followed; a crooked road only trafficked by horse-drawn sleighs during the winter. The ski track consisted of those sleigh tracks and where the horses ran, where they’d also left their droppings!

With a time of 4.10.30, Jonas Persson from Arbrå arrived first in Evertsberg where flags were raised and all inhabitants had come out to watch. He would have been the first winner of the Hill prize, except it wasn’t invented until 1970. Strål Lars was still second but Ernst Alm was only in 20th place. Some stopped longer to eat while others hurried on. Per Erik Hedlund and Oskar Lindberg stopped and took it easy at the food tables. But Ernst Alm ate little and sneaked on…

Per Erik Hedlund commented, much later, on this apparently decisive moment in the first Vasaloppet: ”No one thought of Ernst Alm, who swept by without anyone noticing him. Oscar and I took our time and when we continued we found that Alm was already four, five minutes ahead. In Oxberg we received the same report. Then we had no chance of catching up, despite the track improving as we got closer to Mora. Towards the end, one of my ski poles broke and Oskar vanished. I lost my temper and went slow for the last bit as I ran out of steam.”

The south-easterly wind and wet snow whipped the skiers’ faces mercilessly during the latter part of the race and new snow iced up under the skis. The course left the road and crossed the Oxberg lake and went via the village road to the shop in Oxberg with the last official time and food checkpoint. Three men arrived there at the same time, 11:20. Jonas Persson was in the lead, ahead of Algot Eriksson from Dala-Järna and Ernst Alm in third place. But soon after Oxberg, Alm left the others behind.

The track from Oxberg passed Gopshus by and the unofficial time checkpoints in Hökberg and Läde, where Ernst Alm held the lead. At Eldris station there was a secret checkpoint that gave warning to the finish line. When Ernst Alm passed at 13:01 his start number 114 was put up on big notice boards at the finish in Mora. It took ten minutes for another number to appear, meaning that Alm had a large lead. At the last secret checkpoint in Selja, hardly four km from the finish, Alm found out that he first. He then held a clear lead ahead of his clubmate Oskar Lindberg.

The Mora church bells rang out 13.30 and a few minutes later some of the 5,000 spectators could see the first man approaching. At the Badstubacksbron bridge a horn was blown as a signal. Down on Hemulån the winner came skiing along and Therese Eliasson, the first Kranskulla, stood by by Badstugatan, passing the victory wreath to Ernst Alm. He skied over Stapelåkern (now the Mora municipal house park) and spurted the last 100 metres up Vasagatan to the finish line by the Gustav Vasa statue. The first winner in Vasaloppet history, and still the youngest, skied across the finish line with a time of 7.32.49, to cheers from the crowd.

(After the fact we can see that four Vasaloppet victors to be stood on the starting line in Sälen on March 19, 1922 at 06.04: Besides Ernst Alm there was also the 1923 winner Oskar Lindberg, the 1926 and 1928 winner Per Erik Hedlund and the 1931 winner Anders Ström.)

The text was updated 2022-09-21